Special Reports

SusHi Tech Tokyo 2024: experience ‘Tokyo 2050’ todaySponsored by The SusHi Tech Tokyo 2024 Showcase Program Executive Committee

Driving autonomous vehicles forward with intelligent infrastructure

Cities that want to benefit from autonomous vehicles tomorrow need to think about infrastructure today, says Mike Beevor, Pivot3.

To butcher a quote from the great science fiction writer William Gibson, “Autonomous vehicles are already here – they’re just not very evenly distributed.” In other words, while autonomous vehicles may not be in your city, they might be in the city next door.

- In Boston, a company called nuTonomy has recently gained approval to test its self-driving cars throughout the entire city.

- Kroger, the nationwide grocery chain, has begun to pilot self-driving grocery delivery services at a test location in Scottsdale, Arizona.

- In Phoenix, a few towns over, Google has been busily testing its self-driving taxi service, Waymo, and will launch it as a full-fledged business this year.

- The federal government recently intervened to stop an overly-ambitious test of autonomous school buses in Babcock Ranch, Florida.

Autonomous vehicles are primed for exponential growth, and all indicators point to that growth beginning to happen sooner rather than later. By 2040, we can expect our highways to be bumper to bumper with over 33 million self-driving vehicles.

By 2040, we can expect our highways to be bumper to bumper with over 33 million self-driving vehicles.

What this means is that cities have a responsibility to understand the future of their transit infrastructure and how autonomous vehicles will fit into its context.

More importantly, they need to understand this context now. Critical infrastructure projects take a long time to get rolling — any new highway, onramp, surface road or bridge that’s planned today will inevitably exist in a future where autonomous vehicles are common.

How can cities ensure a smooth ride into the future? What does the underlying IT infrastructure need to look like to support these efforts now and in the future?

Will self-driving cars achieve symbiosis with smart cities?

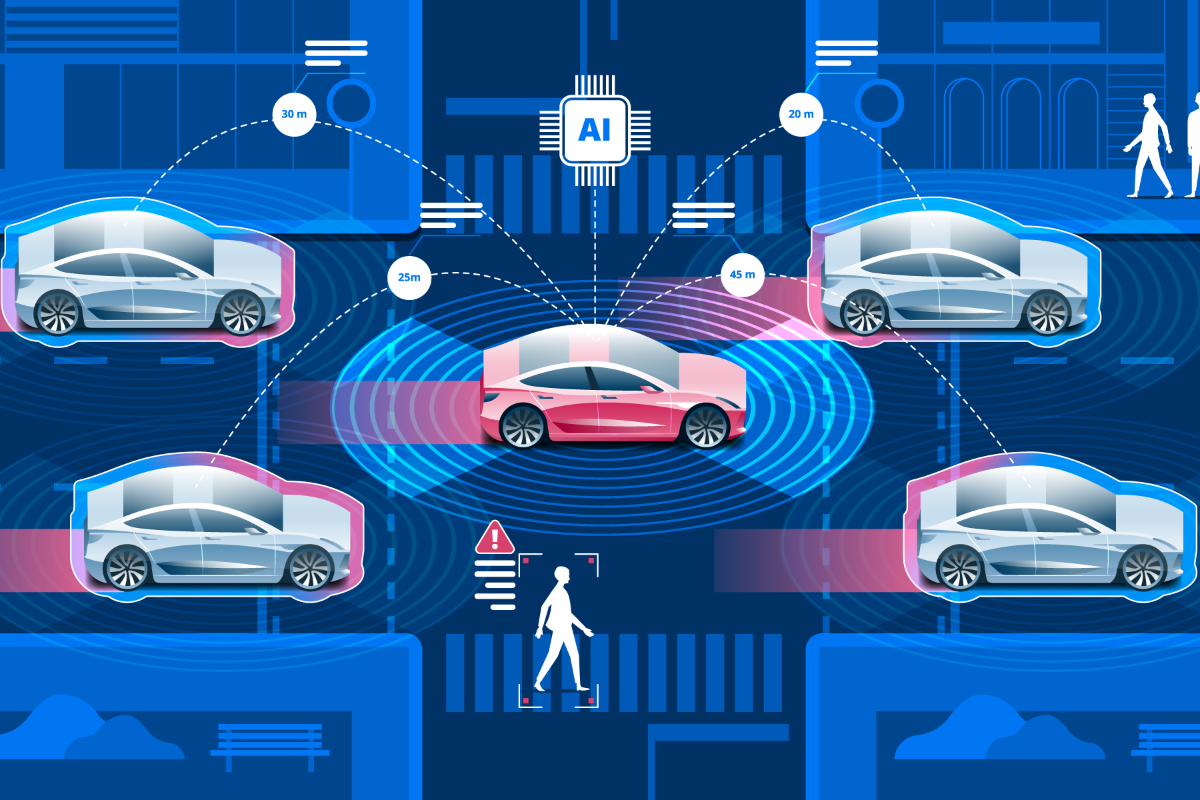

As cars are becoming more autonomous, cities are becoming more intelligent by using more sensors and instruments. To drive this intelligence forward, smart city IT infrastructure must be able to capture, store, protect and analyze data from autonomous vehicles.

Autonomous vehicles could greatly improve their performance by integrating data from smart cities.

Similarly, autonomous vehicles could greatly improve their performance by integrating data from smart cities. In smart city planning, stakeholders must consider how they will enable the sharing of data in both directions, to and from autonomous vehicles, and how that data can be analysed and acted upon in real-time, so traffic keeps moving and drivers, passengers and pedestrians are kept safe.

This means that a city needs physical infrastructure to handle the growing numbers of autonomous vehicles that will be on the streets and an IT infrastructure that can easily manage data storage, performance, security, resilience, mobilisation and protection from a central management console.

Roadside sensors

For example, there’s a case to be made that cities should already be building networks of smart sensors along the roadside.

These would have the capability to measure traffic conditions and potentially even monitor obstacles such as fallen trees, traffic collisions or black ice.

Fully autonomous cars (and even modern GPS systems) would be able to ingest this data and make intelligent routing decisions, planning routes that would avoid obstacles, from static and reliable sources.

Instead of performing numerous onboard calculations about traffic patterns and routes using data from other vehicles, autonomous cars could simply receive this data as a small packet from a roadside sensor, perhaps half a mile down the road they are travelling along.

In the opposite direction, data from the car, transmitted to the sensor, could be forwarded directly to a data centre for long-term study. This would free up precious GPU resources onboard autonomous cars, leaving more processing bandwidth for mission-critical, real-time response activities such as collision avoidance.

In some instances, this data could be literally lifesaving. Autonomous vehicle testing was widely put on hold recently after a pedestrian was killed when a self-driving Uber vehicle failed to identify her as she was crossing the street.

Cities could use their sensor network to monitor pedestrians in real-time. Cars could use this data to start slowing down automatically when pedestrians are crossing the road ahead, before LiDAR (light detection and ranging) even detects them.

Benefits to cities

By the same token, cities could greatly benefit by ingesting and analysing data from autonomous vehicles.

Each self-driving car is essentially a flight data recorder for roads, recording every slowdown, every pedestrian, every bump and every nearby car. Cities could use this information to do great things:

- Cities could tap into LiDAR data to get a complete map of their roads — including every pothole and frost heave. This would enable them to save money by deploying their departments of public works in a more efficient manner, triaging the worst and most urgent damage.

- Self-driving cars could replace traffic cameras, especially while we exist in a hybrid world of autonomous and human-controlled vehicles. By recording nearby cars, self-driving cars will inevitably pick up on speeders and reckless drivers. By sharing this data, they would allow cities to mitigate these drivers and even generate revenue via speeding tickets. It may not be popular, but it would improve safety.

- Many self-driving cars will operate on a taxi model, remaining in continuous circulation by picking up and dropping off passengers. Since these cars rarely need to park, cities could stimulate economic development by bulldozing a certain number of their parking garages and re-zoning them as commercial or residential buildings.

By using self-driving cars as mobile instrumentation clusters, cities could gather information that could save lives, improve quality of life and even drive economic development. However, again, this is easier said than done and there are some obstacles in the way.

Data-sharing between self-driving cars and smart cities

First, although each would benefit, there’s currently no clear-cut operational standard for cities and cars to share data.

Typically, the avenue for this data-sharing to take place would be set by regulatory agencies such as the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB)

But, the current administration has taken a laissez-faire approach. In order to achieve data sharing, cities may need to approach self-driving car manufacturers and operators individually.

There’s currently no clear-cut operational standard for cities and cars to share data.

Second, cities are in no way prepared for the volume and complexity of data that self-driving cars will generate. During an average day, each self-driving car may produce more than 4 terabytes of data. There currently exists no practical way for cities to transmit, store, and analyse this data.

Here, cities can kill two birds with one stone. By investing in the infrastructure needed to support self-driving cars, cities can put themselves in a position to negotiate access for the data they produce. One of the major tenets of IoT is the ability to monetise data, especially in a smart city in order to reinvest those funds in regional improvements.

It has long been held that smart cities should realistically be working under the premise of smart regions.

Namely, this means helping to create the network of small-cell 5G transmitters that will support self-driving cars alongside the edge computing resources that will help these cars make critical decisions away from centralised data centres. Although this may seem like an expensive investment, many smart cities are planning to do this already.

These concerns around data-sharing and network creation again raise the question of what kind of infrastructure is needed to support these capabilities as they both come online and as they ramp up. The reality is that all of these conversations are just theoretical, but the need to prepare for them isn’t.

Autonomous vehicles are coming; the rest is just details.

Autonomous vehicles are coming; the rest is just details. Cities that want to cash in on these smart trends need to be investing today in infrastructure that gives them the flexibility to follow wherever these trends go if they want to be in the driver’s seat.

You might also like: